“The light bulb is important as it is the last piece of fire”

I interviewed Ingo Maurer in 2011 for FT Rui, and again covered his show in Milan for AD China in 2016.

There is no doubt that lighting speaks to our senses in a more subtle, insidious and primal way than any other form of design. Yet in most people’s homes, offices and far too many public spaces, it is reduced to an afterthought, if that. At an architectural level lighting is often determined by the rigid demands of maintenance and legislation while consideration for interiors is normally confined to a narrow set of archetypes that have not evolved to fit contemporary technology or living patterns.

Many designers have identified and challenged this situation but one name consistently emerges as leading the way in all that is both innovative and expressive: Ingo Maurer. Rather than stick to established forms of lamps/shades and technology, Maurer has been tirelessly reinventing the whole field for close to 50 years. Now with a team of over 70 staff at their Munich HQ, his company creates everything from desk lamps to schemes for fashion shows (Issey Miyake in 1999) and subway stations (Munich). While some of these may feature highly functional, efficiency-driven solutions, often with an engineering aesthetic, these co-exist quite happily with other parts of the collection which may incorporate ‘found objects’ such as feathers, plastic birds feet, broken shards of porcelain, tea infusers, toothpaste tubes, soup cans, as well as exotic and unlikely materials such as exposed circuit boards, gold leaf, and holographic film.

I met Ingo Maurer at Milan’s Spazio Krizia; the gallery at which he has become a regular fixture during recent design fairs, showcasing new work from his own company as well as that of other like-minded lighting designers. This year’s exhibition was as surprising as ever, featuring among other things a twitching robotic desk lamp, an illuminated wallpaper, a cluster of electronic candles and a giant illuminated green sponge, ‘Biotope.’ In these surroundings, the designer discussed his experiences in design and production since the company’s beginnings in the early 1960s. His first involvement with the Fiera was in 1968 and while many things have changed, it remains for him the most important event in the design calendar “that period was the high point for Italian Design, but Milan is still the centre of design. You have London now, but nothing can match the variety of Milan. When you start a company, it takes a couple of years until you are really recognised, especially in Germany, but here we were recognised very very fast.” This international reach has led to confusions of identity in the past; the playful and poetic nature of his work contrasting with the strict and formal image of German design abroad: “Yes, I am always taken for an Italian not a German, but I am a German. The quality comes straight from the head or the heart or from whatever part of the body and I am very great on taking risks at all levels in life, so new aesthetics and pushing boundaries is really what I and my team are doing with so much passion all these years.”

It is this risk-taking that almost put an end to the company in the 1980’s when Maurer sunk all available resources into the development and production of a novel system of track lighting known as ‘YaYaHo.’ While other designers had worked on similar deconstructed approaches, it is Maurer’s version that has endured, becoming the success that set the business on its feet: “Like every company things were going up and down, but with that one product, we invested all we had, and I was more or less bankrupt, but it took off like mad.” While the system is outsold by its copies many times over, nothing matches the quality or character of the original which is not only still available, but still being developed (this year new white silicone shades have been added to the collection of components).

New products, particularly those incorporating new technologies, take time to evolve, and many of the things on show are only just becoming available after much development. One popular example is the ‘Looksoflat’ desk lamp. A collaboration with Stefan Geisbauer, this playful interpretation of a classic task lamp takes advantage of the compact nature of new lighting technologies – in this case LEDs – to create the image of a lamp that is almost flat. But despite the relative maturity of LED, it was still not a straightforward project to realise in production terms: “We had to fight and we are still fighting in terms of price, but now it is a product and we have a larger volume, we can make it available finally.”

The difficulty in bringing such a project to market does not put off the veteran designer, who is as excited about new possibilities as ever. With the latest buzz in the industry surrounding so-called Organic LED (OLED) technology, it is no surprise that Maurer has also incorporated this into his work: “After being the first to incorporate LED into our designs, we were the first in 2006 to use OLED in pieces called Early Future and Flying Future. ….I was the first one who dared to do something with this new technique and we still work on it… it’s still too expensive and I don’t think this will substitute any kind of light, but it will add to the diversity – things from which we can choose for the right light.”

It is this attitude to technology that gives the collection its permanently refreshing feel. While others would choose to hide the circuitry and mechanics, Maurer finds this intrinsic to the overall beauty of a piece and wants to share it: “For the LED wallpaper, my factory can not do that [the surface-mount LED process] but we make the lines where the LEDs are going to be. I am very crazy about those lines. I have often used circuit boards in our designs. I am very crazy about this aesthetic. I LOVE it. I have always tried to avoid any kind of hiding something which is important. People thought that the circuit board is something ugly, and I took the circuit board enthusiastically and made products or special installations by exposing it.”

This relationship with technology has another side, though, in the designer’s equal passion for older lighting technologies which have fallen out of favour because of energy consumption issues. “I really hope we are not really drowning in LED or OLED in 10 years. I am really sad to see the end of the incandescent bulb. It’s absolutely terrible to take away this fantastic beautiful icon which changed our lives so much.” Although alternatives are improving all the time, they are really no match for the straightforward bulb: “Yes they are getting better – but it [LED and compact fluorescent] is a very monotonous light. The light bulb itself is important as it is the last piece of fire. Light started with fire. Over the years it developed with gas etc. and the Wolfram [Tungsten] thread is fire.” Maurer is not alone in the desire to maintain this primal link, but he is perhaps one of the more active and outspoken campaigners [in 2008 the European Union voted to phase out the traditional light bulb]. “I am fighting for the light bulb; we, too, are conscious of energy, but I think in spite of this, the EU did a very bad decision and I don’t think it will last. I had an exhibition in which I called for an uproar against this decision. And I had an exhibition showing two identical rooms with two different lights and the saving light has many disadvantages, and one of them is really the when you want to dispose. People are not always strong enough to bring it to a place to dispose properly.”

This includes the production of the ‘Euro Condom’ a bulb-shaped silicone sheath “to protect yourself from stupid rules.” The is not surprising given that the iconic bulb shape has been the starting point for many of his most recognisable pieces including one of his earliest table lamps ‘Bulb’ from 1966 (still in production), and perhaps the most recognisable, ‘Lucellino’ – the flying feathered bulbs – from 1992, which for the last 6–7 years have incorporated the company’s own halogen bulb replacement. This has since been joined by WoonderLux (2010), an apparently empty bulb, which has a concealed LED light source in the threaded base. While these objects maintain the image of the tungsten bulb in a form, the decision by so many countries to phase out the older technology adds additional poignancy to the magical piece ‘Wo bist du, Edison, …?’ (Where are you Edison) from 1997 – featuring the ghost of a non-existent light bulb in a circular hologram. This theme of destruction and deconstruction has surfaced before in the exploded shards of porcelain that make up the ‘Porca Miseria’ lamp, and, along with some of the more expressive or experimental works, have prompted questions regarding Maurer’s motivations; some would situate his work alongside others who have staked a claim to a supposedly new territory of ‘design art.’ Fortunately, Maurer, is in no such doubt: “I have no pretensions whatsoever – no pretension to make art. I am a maker, and I have imagination, ideas, but I think I cannot stand pretentious products. I just don’t like pretentious things.”

Whatever label is applied to his output, it is a phenomenally complex operation including all areas of design, research, production, distribution, retail, promotion. The ability to manage all this, Maurer puts down to his team: “I have an absolutely great team, which I couldn’t do without. All great individuals. Production is maybe the hardest part of doing it. It is very hard. And I want to have my 74 people to feel like a family. And I don’t differentiate between designers and the people who pack and ship [the products]. Everyone contributes.” Into this busy schedule, Maurer is somehow able to fit numerous international projects, including China: “I love visiting China. I worked for 15 years in Hong Kong, where there are many collectors of my work and I’d love to do more work in China, but we are working around the globe – Brazil, New York, Texas so there is not always time.” This most recent project is at renowned Temple Hotel in Beijing; “it is only a little hotel, but it is a very super place, very magic, and there is a large temple and small temple involved. My vision for it is not being aggressive. For me it has to be a calm place where you can think and you have conferences. Now with the new technologies, you can have super-bright light, but I want a subdued, tender feeling because a lot of good things are killed with light.” The 600-year-old site has functioned as a place of worship, headquarters of religious thought, printing press and, apparently a television factory where the first Chinese colour TVs were produced. More recently it has been transformed; layers of alterations stripped away to uncover a beautiful temple complex, much of it in original condition. The buildings, survivors from another age, are well complimented by Maurer’s lighting master plan and are augmented through his more iconic creations, including which often feel other-worldly in their mix of materials and forms. More ambitious still is the work Maurer has planned for the Inhotim Park in Brazil. Unveiled at this year’s Milan fair, this architectural installation will take the form of a giant cracked egg – the cracks and entrance giving way to a dramatic lighting scheme. This form has been a motif of Maurer’s work for a long time, and a similar concept was the basis for a suspended lamp designed in 1996. The new piece, which has been likened to an alien spaceship, will sit in the parklands of the Inhotim museum where it will join other works by artists such as Anish Kapoor, Doug Aitken and Matthew Barney.

The designer views installations such as this as a chance to experiment and collaborate with others and it is this constantly evolving approach that makes a visit to the Ingo Maurer showrooms in Munich and New York so rewarding. Recent events involve completely re-furnishing the Munich showroom with Styrofoam as well as performance art incorporating light. This enthusiasm is also evident in his collaborations. Always at the forefront of technical innovations, it was inevitable that he would cross paths with the designer and engineer Moritz Waldemeyer (who has created wearable lighting for performers Rhianna, U2 and Will.I.Am amongst others). One of the most popular exhibits at the fair was their recent collaboration – a cluster of electronic candles. These re-visit an existing Maurer design – the seemingly magical suspended ‘Fly Candle Fly,’ except the new version incorporates tiny LED displays that play a film of real candle light. The result is realistic and hypnotic and a triumph of electronic engineering.

Maurer’s appetite for experimentation has seen the company produce work that embraces every conceivable form of light from candles to neon to fluorescent to OLED, and soon, it seems, even lasers: “I have a new job to do Tristan and Isolde at the New York City Opera. And there, in a certain part I will use lasers. It is a new concept of the opera. I was surprised that they came to me and asked for a proposal, but they liked it.” With such an array of light-producing technologies at his disposal, does anything remain that the designer wishes he could incorporate into one of his lamps? The pressures of running a business appear not to have dampened Maurer’s imagination or enthusiasm for what might be around the corner: “If all this could be achieved without the complications, that would be the ultimate. I would like to snap my fingers and there would be light and it would go zzzzhhhhhuppp and bbrrrruuuup like that.”

Portrait of Ingo Maurer with XXL Dome by Ben Hughes

Ingo_Maurer_Portrait_2.JPG

Golden_Ribbon_Showroom.jpg

Lighting installation in gold plated sheet metal. Design: Ingo Maurer.

Photo: Tom Vack

NewYorkShowroom_01.jpg

Ingo Maurer New York Showroom

Photo: Tom Vack

LED_Wallpaper.jpg

LED Wallpaper, designed by Ingo Maurer, produced by Architects Paper. Available in Red, Green and White.

Photo: Tom Vack

YaYaHo_Element16.jpg

“YaYaHo” trapeze lighting system. Design: Ingo Maurer. First introduced in 1984, this is the company’s most iconic product. This white silicone shade is a new introduction for 2012.

Photo: Tom Vack

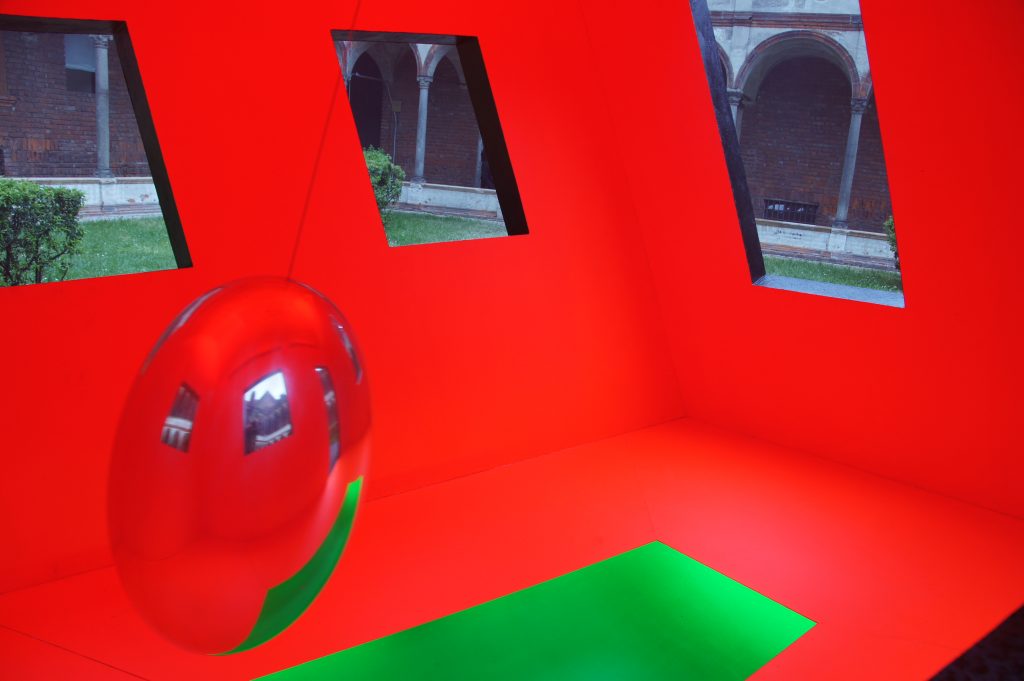

Spazio_Krizia.jpg

Ingo Maurer Installation in Spazio Krizia, Milan.

Photo: Tom Vack

Zettelz_Insects_Detail.jpg

“Zettelz Insects” lamp by Ingo Maurer. Stainless steel and Japanese paper.

Photo: Tom Vack

Spirits_Flying_High.jpg

“Spirits Flying High!” – a “Lighting Carpet“ made from a special combination of synthetic material and LEDs.

Photo: Tom Vack

maurer_at_temple_hotel01.JPG

“Oh Mei Ma” lamp in Temple Hotel, Beijing

Photo: Ben Hughes

maurer_at_temple_hotel10.JPG

“Birds, Birds, Birds” at Temple Hotel, Beijing

Photo: Ben Hughes

maurer_at_temple_hotel19.JPG

“Bibibibi” table lamp at Temple Hotel, Beijing

Photo: Ben Hughes

JohnnyB_Butterfly.jpg

“Johnny B Butterfly” Lamp by Ingo Maurer. Bulb with white Teflon shade and hand-made insect models.

Photo: Tom Vack

Looksoflat_.jpg

“Looksoflat” Lamp by Stefan Geisbauer, produced by Ingo Maurer. Aluminium, available in Black and Silver

Photo: Tom Vack

Looksoflat.jpg

“Looksoflat” Lamp by Stefan Geisbauer, produced by Ingo Maurer. Aluminium, available in Black and Silver

Photo: Tom Vack

Candles_03.tif

Electronic animated LED Candles by Moritz Waldemeyer with Ingo Maurer.

Photo: Moritz Waldemeyer

Munich_Showroom_07.jpg

“Styrofoam World” Installation in Ingo Maurer Munich Showroom

Photo: Tom Vack

Munich_Showroom_10.jpg

“Styrofoam World” Installation in Ingo Maurer Munich Showroom

Photo: Tom Vack

EL.E.DEE 1.jpg

“El.E.Dee” lamp by Ingo Maurer

Photo: Tom Vack

Porca MiseriaRot.jpg

“Porca Miseria” Lamp by Ingo Maurer

Photo: Tom Vack

Birdies_Busch.jpg

“Birdies Busch” Lamp by Ingo Maurer

Photo: Tom Vack

Wo bist Du Edison-Detail.jpg

“Wo Bist Du Edison” Lamp by Ingo Maurer

Photo: Tom Vack

Wo bist Du Edison.jpg

“Wo Bist Du Edison” Lamp by Ingo Maurer

Photo: Tom Vack