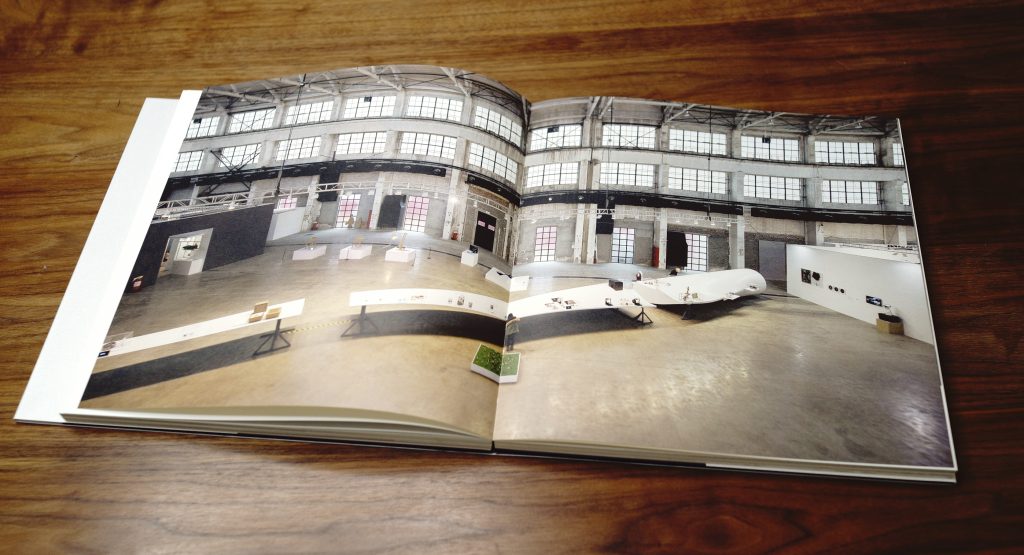

I was asked to curate a 1000m² space within this giant aircraft-hangar space on the West Bund. The centrepiece was a 40 metre bamboo composite wind turbine blade from a 1.5MW turbine developed by a Beijing company, Khanwind. It was an amazing experience. This essay describes some of the contents and thematic links between some of my favourite designs of recent years.

The essay was published in Chinese and English in the catalogue of the 2016 Shanghai Art Design Biennial, Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House p.171–217

ISBN 978–7‑5322–9016‑1

The future of today is a slightly less inviting place than it was 80 years ago, or even 40 years ago. For most of us, the sense that advances in technology will overcome mundanity in our daily lives and lead us to a new path of happiness through leisure is gone. In the intervening years those myths have been more or less exorcised in a blur of cynicism, popular culture, developments in sociology and the new wave of science fiction. We got hold of a lot of the technology, and it improved a lot of things, but it has it didn’t necessarily make life easier, or happier. We now recognise the future as probably looking much like the present but with even more technology. And even more technology problems. As if to confuse the matter further, this anxiety filled path to Modernity is nothing new. It is very old, yet it has a strong hold in our psyche — one which refuses to go away.

The modern world has changed radically in many ways over the past two hundred years; but the situation of the modernist, trying to survive and create in the maelstrom’s midst, has remained substantially the same.

It is the fate of the designer to battle through this maelstrom and negotiate this journey to whatever lies at its end. It is a question as much about philosophy and disposition as it is about science and technology. Many imagine a perfectly even, crisply paved route to a gleaming bright and shining vision. Others, perhaps more realistic, see an uneven track with many side roads.

Emblematic of this loss of innocent belief in a bright and monolithic future is ‘The Infallible Answer’ by artist Sean Mackaoui. This is a grown-up version of the robot that inhabited a quiz game called ‘Magic Robot.’ While the original gave answers to pre-prepared questions through an ingenious magnetic mechanism, this version is conspicuously lacking any wisdom, knowledge or anything bar the most rudimentary mechanics. The original game was popular from the 1950’s when speculation about the the future was popular and full of promise. This version is very much of its time and betrays a cynicism of a simplistic future narrative.

Perhaps more unnerving than this unclad Mechanical Turk is the installation that confronts visitors at the entrance of the exhibition by British studio Freshwest. Two identical chairs on identical plinths; one of which has a built-in sensor triggering an instant collapse as the viewer approaches. After a few moments the chair’s demeanour becomes more stoic as it begins pick itself up. The mechanism, based upon the small wooden animal toys which collapse when pressed from beneath, becomes clear after seeing the effect. For designers and architects a chair is the ultimate expression of an idea in human scale. The idea could be about materials, joints, movement or posture. Or, as in this case, it could be an abstract idea — what would happen if a chair had a personality? The surprise elicited by the sudden collapse of one of these chairs is a reminder that not all technology is reliable, friendly or useful.

The viewer, confronted with these two chairs is prompted to make a choice between the intelligent but belligerent version or the dumb, but reliable version. It is clear that there is not just one future, but an infinite number. The path chosen is a collective decision, made in tiny steps, but influenced in some ways by design.

Just beyond the belligerent chair we find the element which forms the backbone of the exhibition, both in a structural and ideological sense. It is a 40 metre long Bamboo and fibreglass composite wind turbine blade. During the exhibition we provide a rare opportunity to see one of these vast components up close. As a sculptural object the purity and elegance of its unending multiple curves is captivating and makes a mockery of the so-called ‘speed forms’ beloved of vehicle designers. While the shape is 100% dictated by function, the material science is much more in keeping with the philosophy of renewable energy than the vast majority of wind turbine blades in service. Although timber composite blades have been used in wind turbines since the 1980’s, this is the first blade to incorporate bamboo. This example was manufactured in 2010 and then cut into parts as part of a stress testing analysis. Other blades in the same batch remain in service on a 1.5 megawatt turbine. Unfortunately fluctuations in the price of renewable energy and a reluctance for innovation in the industry means there are only 6 sets of bamboo blades currently in use in China.

As the largest single exhibit, this piece drives home the point that putting aside designers’ obsession for technology and lifestyle, the absence of sustainable thinking is the single most important issue facing the industry and society at large. While multiple futures are possible, one that is not underpinned by sustainability is destined to be unstable and short-lived.

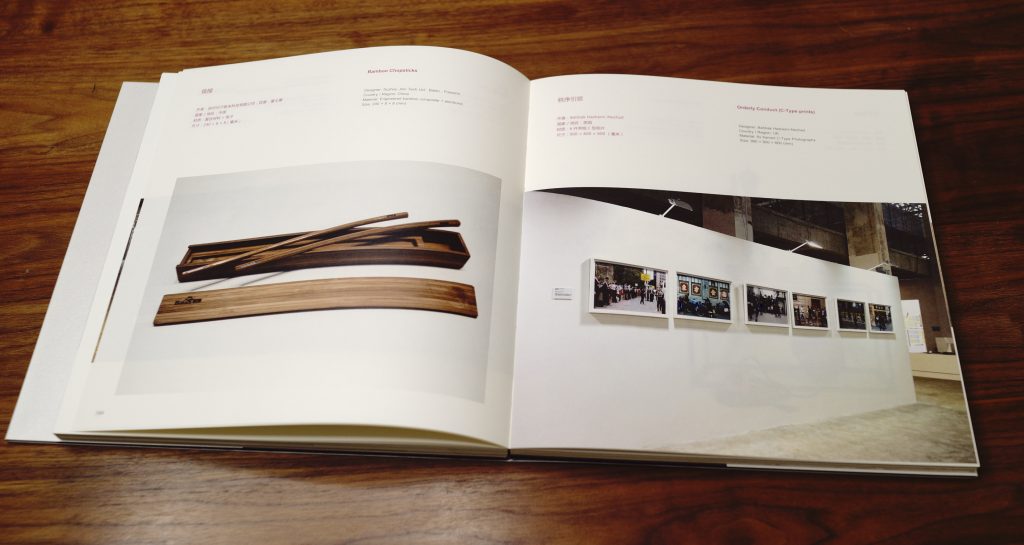

Located at the very tip of the largest exhibit, we find the smallest exhibit — a pair of engineered bamboo chopsticks with embedded analytical technology. The circuitry will detect harmful impurities and also alert the user if the food they are handling may be too hot.

Not only are these the smallest exhibits in the exhibition, but close inspection finds that they are made with the same material, same process and by the same company as the largest exhibit, the wind turbine blade on which it sits. This showcases both the versatility of modern Chinese manufacturing as well as the almost magical properties of bamboo, which is as important to us now as when we first encountered it as a species.

In the absence of a clear future vision we have at least plenty of places to look for alternatives. One of the best places to get a glimpse of our future is through the narratives of science fiction and the parallel musings of futurology community, which has become a significant field in its own right. The futurologist generally has one eye on trends in the cultural sphere, one eye on developments in technology, whilst at the same time trying to keep their balance on the ideological pathway they have chosen. In this exhibition I would like to promote the idea that it is in art and design that the future is given form in both a speculative as well as a concrete, commercial sense. Designers create the material culture through which we live our lives but they also create concepts and scenarios that show alternatives that might be around the corner. One of the principle directions that emerges from the current landscape is that thanks to a number of converging trends, the design world is more vibrant and accessible than at any other time. The tools of design and production are not just in the hands of a tiny minority with a narrow view of the world; they are available to almost everyone who has access to a computer, an idea, and a great deal of stamina and tenacity. This has been described as a ‘Liquid’ modernity, where the institutions of the past give way to a more lightweight and nimble agent.

Several exhibits demonstrate this lightness and fluidity, often in response to swiftly changing market conditions. Two examples relate to one of the unwanted side-effects of progress: the chronic air pollution with which many in China and around the world are having to endure. As awareness has grown of this problem, users have sought ways to access information and effective air purification. One such device was designed by a small team put together by entrepreneur Liam Bates. He was living in Beijing when his fiancee, Jess, developed symptoms of asthma. After searching unsuccessfully for a suitable air purifier, Liam decided he had no choice to develop his own. The Laser Egg is a follow-up product — a smart networked air quality monitor that gives users the ability to remotely measure air pollution levels both indoors and outdoors. In a similar vein is the cardboard IAQ air purification filter by Li MingHu. This is a very simply engineered product that addresses a growing demand for low cost domestic air filtration in China’s polluted cities. It incorporates standard parts in a simple enclosure made of cardboard. Despite the cheap materials, it demonstrates clear fitness-for-purpose and even has an attractive pierced air intake inspired by traditional window designs. If air pollution is a temporary issue in China, it is appropriate that a device such as this uses cheap and simple materials. Mr Li’s enterprise exemplifies the kind of highly responsive cottage industry that has been able to flourish in China in recent years through direct internet sales. It is this creative and entrepreneurial spirit in the face of clear user needs that builds dynamic new businesses.

But progress brings with it cultural as well as physical conflicts. A number of projects in the exhibition consider what happens when cultural practices fails to keep up with changes imposed by technological progress. Examples include religious observances, dancing in public and even the rituals associate with tea drinking. One highly innovative project in this area considers the history and development of matchmaking in China and the way that rapid economic and social change has affected this. In the past, marriage partners were organised by parents, communities and even work units. Nowadays young people want more freedom in their choice of partner, but society — their parents and grandparents in particular — has not caught up so fast. The designer undertook research with marriage-age subjects as well as visiting and conducting interviews in locations traditionally used by relations to seek suitable matches. The resulting proposal is a clever twist on a matchmaking protocol — a downloadable fan that contains encoded information about the user’s profile. This is then used by their grandparents and possibly parents as a prop to seek suitable matches in public spaces. It incorporates high and low-tech elements and surreptitiously tackles the more fundamental underlying problem of communication across generations.

Potentially one of the most controversial exhibits is also one of the most unassuming. In China, where food and mealtimes are close to sacred, it is hard to imagine doing away with the whole ritual of cooking, serving and sharing meals. Yet this is exactly what increasing numbers of post 90’s generation is starting to do in the USA. Soylent is a ‘meal replacement’ drink. It was created by software engineer Rob Rhinehart in California’s Silicon Valley in response to his observation that many of his colleagues had unhealthy diets because of their work lifestyle — many considering food to be an inconvenience. His background led Rhinehart to develop the product using processes more normally associated with technology startups — it was researched by applying an engineering style analysis to food; it was crowd-funded through a website called Tilt; its ‘code’ (or recipe) is open-source and available for anyone to make themselves and it was first introduced to the public as a ‘beta’ release. It even has a geeky name: “Soylent” refers to a 1973 science fiction movie, Soylent Green, in which the members of a future society exist on a homogenous, centrally produced liquid diet. It is engineered to contain all the necessary energy and nutrients necessary to live a healthy life. Its nutritional profile is based on international standards and includes all the necessary protein, carbohydrates, fats, fibre, and vitamins and minerals needed by the human body with limited contribution from less desirable components such as sugars, saturated fats, or cholesterol. It is approved as a food by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

While the concept of consuming a liquid with a ‘neutral taste profile’ in place of a meal is horrifying to many, it has sparked an interesting debate about nutrition, health, lifestyle and sustainability. Rhinehart makes the case that conventional food production is extremely inefficient and creates a huge strain on natural resources while his alternative is vegetarian, even vegan: Soylent 2.0 has 50% of its fat energy originating from farm-free, algae sources. In another nod to its programming heritage, the company manages a free online forum and interface where users can develop their own variants at home. These can be compared with others’ creations for their nutritional make up, taste, convenience and cost. This has brought a sophisticated knowledge of nutrition to an audience that had not taken it too seriously in the past.

It is especially poignant to present these works in a metropolis that has had its own struggle with modernity and conflicting versions on the future. This is embodied even in the city landscape: the passive feminine yin of Puxi contrasting with the masculine, formal and imposing yang of Pudong. Here, the city’s emblem, the Pearl TV tower, stands proudly above them both. Already anachronistic by the time it was completed in 1994, this is a constant reminder of a compromised Jetsons-style future that has yet to materialise while visitors tend to prefer the once-forgotten, and more human scale meandering streets of the French Concession on the other side of the Huangpu River.

Depictions of the future typically conform to an extreme version of one of two scenarios; one where a high-tech monolithic entity is bent on control at all costs, or one where we have returned to a pre-mechanical pastoral life, precipitated by a breakdown in technology. This exhibition allows us to escape from these two undesirable visions and celebrates a third direction where technology remains a key part of our life but as an enabler rather than an oppressive force. This is a playful, diverse and interconnected world where devices developed by multinationals interface with locally developed solutions by enthusiastic amateurs, artists and designers. There is a joy in the potential of sustainable technology and a celebration of the fact that the industry giants of the future might be the kitchen table tinkerers of the present. Some objects are speculative and tell us about a possible future existence — where technology adopts human characteristics and interfaces with human senses in new ways; others are real products — in development or already available — that show a brighter and more diverse vision of the future where design can play a positive role in countering some of the negative effects of the relentless quest for progress..

Thanks to Ding Yi 丁乙 for inviting me to take part and everyone involved in the exhibition including: Marcus and Simon at Freshwest, Google, Baidu, Ingo Maurer, Dyson, Simon Morse, Sean Mackaoui, Nick Bonner, Dominic Wilcox, Li Naihan, Zhang ZhouJie, Midea, Makey Makey, British Council, Sugru, Nick Ross, Huang Weijun, Liu Zhizi, Li Penghao, Weng Xinyu, Jay Silver, Eric Rosenbaum, Stephen Hayward, Anna Couvert-Castéra, Wang Pan, Oluwaseyi Sosanya, Bahbak Hashemi-Nezhad, Khanwind.