Published in September 2007, this article is a review of the Camouflage exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum.

Sun Tzu tells us in The Art of War: “All warfare is based on deception… When near, make it appear that you are far away, when far away, that you are near…” makes sense.… Why then would the armies of the 19th Century dress up in such bright, garish colours? Surely this made them easier to spot? Much more sensible to wear something that would blend in with your background, so that you could creep up on your enemy and surprise them? Similarly incomprehensible was the military tactic of organizing your fighting units in strict blocks… surely that made an easier target? The painted toy soldiers that occupied the imagination and pocket-money of some school friends therefore held little interest for me. What I failed to realize, however, is that the bright colours were designed to make the soldiers stand-out. It was about impressing and intimidating your enemy (as well as helping to identify which side everyone was on), rather than hiding from them. Maybe not so stupid, after all? However, this tactic soon became redundant when weapons technology in terms of range and accuracy advanced to the stage when standing in a field wearing a crimson tunic no longer seemed like a good idea. Even less so when your opposition is flying around in an aeroplane looking for things to drop bombs on. Following this watershed, armies quickly adopted more drab, dull uniforms, and looked at ways of concealing equipment and installations to deceive their enemy. It is this era that forms the opening section of the Camouflage exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum (until 18th November). This has proved extremely popular with visitors, partly because while the exhibits might not be as imposing or as the guns, bombs, submarines and other blunt instruments of warfare on display elsewhere, they show the process, or strategy behind it, in an accessible way. It is also an element of military know-how that has very much filtered into everyday life. It is hard to believe that the first piece of camouflage uniform appeared less than 80 years ago, yet chances are, if you have any interest in fashion, you probably have a piece sitting in your wardrobe right now. Even if you don’t own any camouflage, you can be sure that if you walk down any street in any town tomorrow you will see an example of it being worn by someone who is not taking part in a military exercise.

In the exhibition we learn that the first experiments in camouflage pattern were undertaken by the French army in 1915 (hence the French name – from camoufleur – to ‘make up for the stage’). This pioneering body was made up mainly of artists, who used cubist techniques to paint disruptive patterns on canvas and equipment to help conceal their position from the air. This prompted the British army to develop teams, again employing artists, including Vorticist Edward Wadsworth, to paint their ships so that German U‑boat captains would find it hard to determine their speed and course. This pattern, which became known as ‘Dazzle,’ didn’t really hide the ship, as such, but supposedly made it harder to target. Historians now believe that its effectiveness was more to do with lifting confidence and morale than actually deceiving the enemy. The dazzle pattern, like later designs, found its way into popular consciousness, though, and in many ways reflected the bold geometry of art deco and the jazz age.

The second world war saw a more sophisticated take on camouflage, with lessons learned from the natural world being employed in a systematic way. It had been observed by naturalists that animals tended to evolve camouflage or ‘protective colouration,’ either by blending in with a landscape or by mimicking another animal or plant. These ideas were used in the development of more successful camouflage, most significantly, the introduction of the ‘disruptive pattern.’ This is the most familiar form, and works by breaking up the outline and shape of an object making it harder to identify. In the exhibition, you can see contemporary instructional films showing how to apply camouflage to your face and helmet in the most efficient way.

Printed camouflage fabric was first incorporated into uniforms by the Italian army in 1929. Since then, hundreds of different patterns have been developed – partly to serve in different environmental conditions, such as desert, jungle, arctic, and partly to help identify and distinguish between different fighting units. Since the Second Word War, innovations such as radar, infra-red and thermal and satellite imaging have expanded the range of things one can ‘see.’ These developments have rendered much of the work of the pioneer camoufleurs obsolete, whilst engineers figure out ways of creating low-flying, or flat, angular aircraft that can evade the new technology.

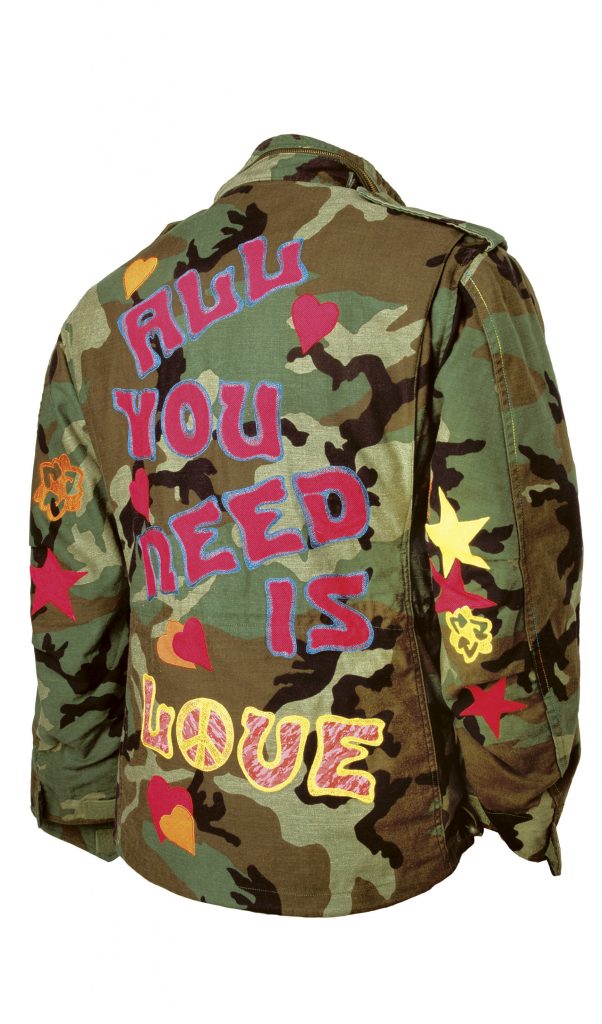

What no one could have predicted was the wholesale incorporation of these patterns into high-street fashion. Paradoxically, military clothing became linked with the anti-war movement during the late 1960’s when US Vietnam veterans wore their uniforms during demonstrations. Army-surplus supply shops also appeared to take advantage of the second-hand market in used military equipment and clothing. This has been associated with a type of thrifty consumer, who is looking for functional clothes at the lowest price, and may therefore be thought of as anti-fashion. Spot anyone walking around wearing khakis or camouflage today, though, and you are just as likely to find a label sticking out that says ‘Diesel,’ ‘Carhartt,’ or even ‘Dior’ as ‘Property of United States Army.’ Camouflage in the street no longer marks the wearer out as a member of the counter-culture. It is fitting, therefore, that the Imperial War Museum exhibition should be funded in part by Maharishi, the London-based label, founded in 1994 by entrepreneur and designer Hardy Blechman, which has profited so much through its use of camouflage in its signature embroidered and customized pieces. The exhibition tells us that these pieces, along with others by John Galliano, Philip Treacy and Jean-Paul Gaultier are intended to stand-out, advertising their presence, rather than being invisible (a reversal of the original design intention). I’m not so sure it’s that straightforward. Is fashion ever really about standing out? When camouflage was first annexed by the 1960’s counter-culture, then by punks in the 1970’s and more recently by hip-hop artists, following the lead of Public Enemy in the 1990’s, it was about drawing attention, doing something unexpected, and making a political statement. Military tailoring, detailing and materials have now been part of the mainstream for 5–10 years and look like remaining so. Don’t think that by putting on your Dolce and Gabbana Pea Coat accessorized with your Michael Kors camouflage tie that anyone will give you a second look or that you are making a statement any more controversial than ‘Hey, I’m rich, and I’m going to war in the urban jungle,’ or something equally banal.

© Ben Hughes, 2007.

Links:

http://london.iwm.org.uk/upload/package/78/site/index2.htm

Images Captions:

Captions in Italics

treacyshoes.jpg

Shoes, designed by Philip Treacy, 2003

©Philip Treacy for Gina Couture Picture 1155

Credit: ©Philip Treacy for Gina Couture

gloves.jpg

Camouflaged Sniper Gloves, P. Tudor-Hart, 1917

©Artist’s estate Imperial War Museum EPHEM 00306

Credit: P. Tudor-Hart

camotower.jpg

The Big Tower, Camouflaged, C W Moss, 1943

Credit: Imperial War Museum

dazzleboat.jpg

SS Argyllshire, dazzle painted, First World War

Credit: Imperial War Museum

maharishijacket.jpg

Maharishi Mr Freedom recycled M65 jacket, 2004

©Maharishi

Credit: ©Maharishi

nikeshoe.jpg

Nike Zoom URL shoe, special camouflage edition, 2002

©Nike

Copyright Owner: ©Nike

Credit: ©Nike

gaultierdress.jpg

Lily Cole wears camouflage ballgown by Jean Paul Gaultier at Paris Fashion Week, October 2006

Getty Images (Photo by Karl Prouse/Catwalking/Getty Images)

Credit: Getty Images

camojacket.jpg

Jacket in Italian camouflage pattern, Second World War

Credit: Imperial War Museum