This is a book by my colleague and mentor, Jane Graves, published May 2008.

Jane taught cultural studies, psychoanalytical theory and sociology at Central Saint Martins for over 30 years and influenced generations of artists and designers. Later on Jane worked as a psychoanalytical psychotherapist, but still had a strong connection with Central Saint Martins.

The book is a collection of 19 essays by Jane and capture her razor wit and analysis in the areas of design and aesthetics. They are as relevant, insightful and funny as when they were written.

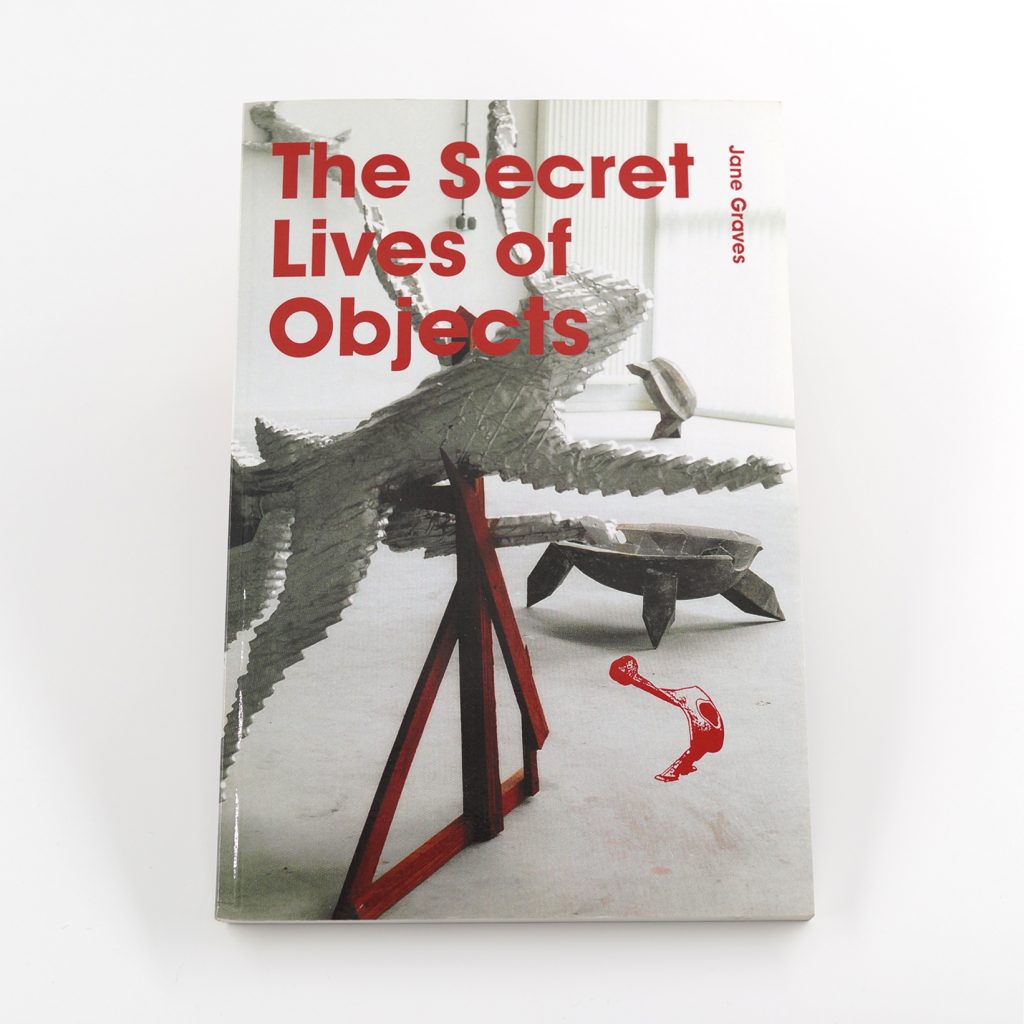

The cover image is a sculpture by Bruce Gernand

The book design is by Sean O’Mara

There is a generous endorsement by Adam Phillips

ISBN 978–1‑4251–7070‑7

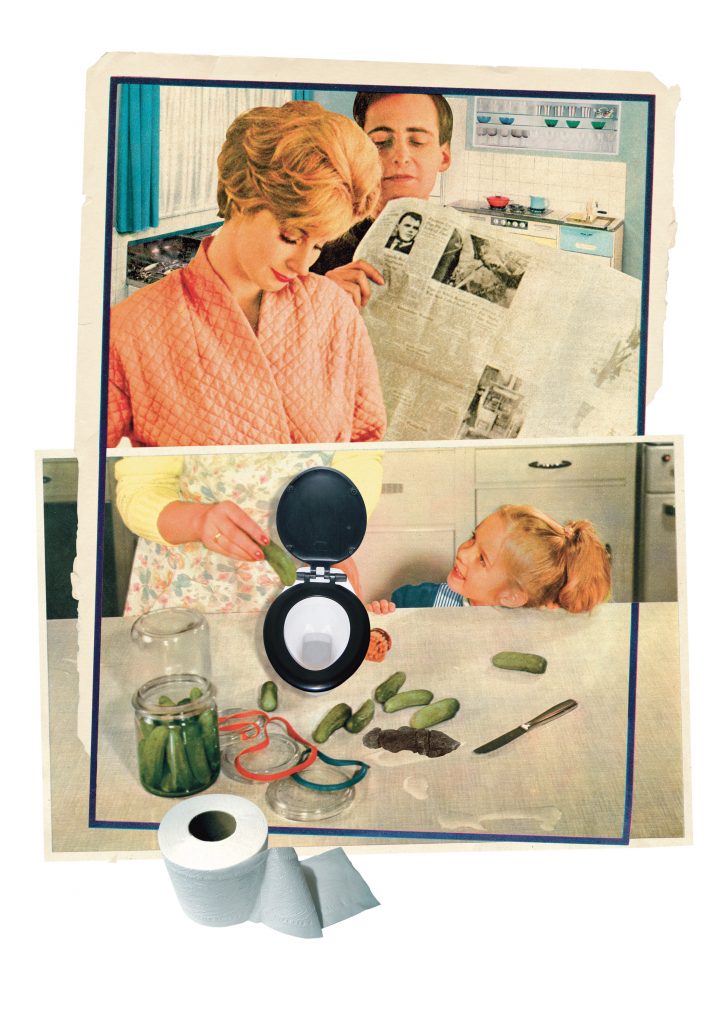

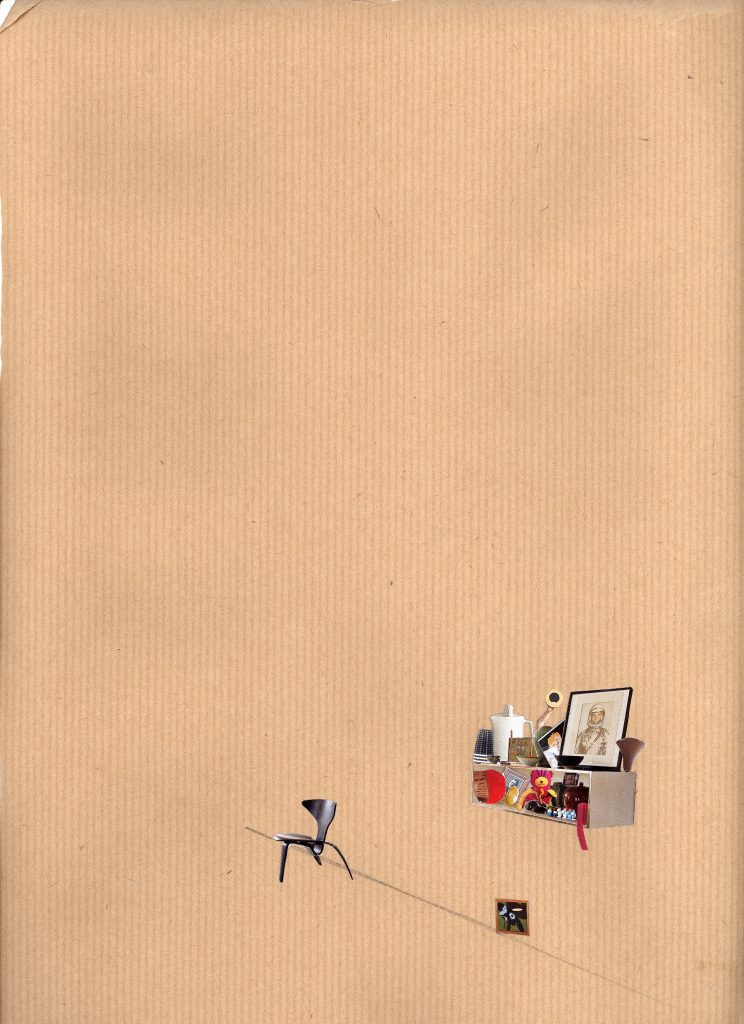

Jane was adamant that she would not work with an external editor for the book as she had a particular vision for it. I helped edit the texts and put them together for publication. I suggested to Jane that we illustrate the book with a series of collages from students and ex-students. She was very enthusiastic about this. I include some of these below. My own contribution was an essay about the use of collage in design — something that I have incorporated in student work for many years. I reproduce this below.

I am sad to report that Jane died on 29th March 2011 at the age of 76.

Collage and the Text/Image Dialogue in Industrial Design

The essays in this book have been illustrated through a series of collages. These are not intended as direct representations of each text, but as a visual record and signpost to the interpretation of a previous reader. Why illustrate a book on psychoanalysis and design with collage? Why not images of the objects themselves? Or not at all? My feeling is that because collage is about mixing up and playing with images they are the best accompaniment to both the layered readings inherent in any object, and the playful approach Jane has taken in the texts. The collages have been created by students, ex-students and tutors of MA Industrial Design at Central Saint Martins – a course with a long tradition of trying to develop the dialogue between a text and an object, or image – thanks, in many regards, to the involvement of Jane Graves over a period of 30 years or more. While cutting things out and sticking them back together in different arrangements sounds like far too much fun to relate to the serious study of industrial design, it turns out to be a technique with a long pedigree that can help both organise and manipulate ideas – particularly for such a group of people, who think in primarily visual terms.

One would imagine the use of collage to be second nature in an age where the notion of authorship has become increasingly remote. Djs, Stylists, Editors, Critics, even Bloggers, while generally less conspicuous, are far more influential in a media-saturated culture where fragments, soundbites and blogs are favoured over structured composition.

For design disciplines that straddle the many boundaries between social science, technology, marketing and engineering, collage is a very potent tool in the communication of an issue, or position. It has been used by those studying MA Industrial Design for many years as an aid to more established, or academic, forms of expression. Students have found it useful not only as an aid to the definition of an area of study, but also as a generative tool that encourages the introduction of elements of creative chance into a design process. The practice of cutting up images to make new ones goes back to the origins of printing itself, but the true power of the process as a tool of mass-communication was only fully realised from the 1900’s when first the cubists, then the Dadaists incorporated it into their practice.

There is some confusion as to the definition of “collage” (literally “glueing”) and its relation to photomontage, which also emerged at around this time, but one can’t help feeling that whether the images originate from the studio or the darkroom, the intention is pretty much the same. One of the most important figures, who experimented with pretty much every technique (and who wasn’t too concerned with labels), was Max Ernst. The appeal of his approach, which often incorporated engravings from catalogues and pulp novels is summed up by André Breton in the introduction to his 1921 exhibition: “It is the marvellous faculty of attaining two wildly separate realities without departing from the realm of our experience, of bringing them together and drawing a spark from their contact; of gathering within reach of our senses abstract figures endowed with the same intensity, the same relief as other figures; and of disorientating us in our own memory by depriving us of a frame of reference — it is this faculty which for the present sustains Dada. Can such a gift not make the man whom it fills something better than a poet?i” This was written some years after the introduction of the idea of ‘ready-mades,’ but the statement could apply equally well to the objects created by Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim and Joseph Cornell which encourage the viewer to re-visit preconceived notions of use-value, décor, sexual identity, nature etc.

As soon as one starts to think of the potential offered by these normally inert, mass-produced objects, the subject really comes to life for students of industrial design. The discipline has always been concerned with an interpretation of material culture and the mechanisms that inform this, but has also been bogged down with tired definitions of what is “acceptable,” or “good” in this context. Objects that embrace absurdity or contradiction, such as the work of Joán Brossa, or Chema Madoz are immediately interesting to students looking for a fresh approach. Collage is somehow a key in both helping to understand this, and as a fast, accessible way of manipulating the ideas.

This is nothing new, of course. As early as 1840, German educationalist Friedrich Froebel used collage in his kindergartens to encourage visual creativity. It was also subsequently developed by Maria Montessori in her schools. Never too proud to jump on a 70 year old bandwagon, the Industrial Design course has, over the last 5 years, evolved a series of workshops for students in the use of collage with recognised purveyors of the medium including Sean Mackaoui and Graham Rawle. These have proven invaluable both in the communication of subject matter, and in the generation of novel ideas. Some techniques involve the simple matching of form regardless of image, and others deal with the construction of a clear visual message. All relate to how designers manipulate concepts in their head, and help to get them down on paper. As projects move on, it is normal for more ‘professional’ forms of expression to take over, but there is lots to be gained by making time to sit down and play with images, with or without an aim in mind. Two designers who have used collage techniques extensively in their work are Emili Padros and Rory Hamilton. Their insights below describe how they have adapted the ideas to their own practice and way of working, as well as the creative freedom, and satisfaction it has brought them.

Turning first to Emili Padros, an industrial designer based in Barcelona: How did he come across this technique, and how has he used it in his practice?

Emili Padros: I have been always very attracted to collage, and in Spain we have big masters of it that I admire, but I actually started using collage when I arrived in London to study (1992). At the very beginning everything for me was new and very different from Spain. I became very curious about English culture and lifestyle, and I started obsessively collecting images from free magazines, Argos catalogues, packaging and all sort of printed media I found during the day. The collage was for me in those days a sort of visual diary. The collage helped me processing all that graphic information, and allowed me recording what I was doing or how I was feeling at that time. In those days I also discovered the scalpel, an indispensable tool for my collages. I became very methodical about it. I could spend long hours cutting out the images I liked and then combining them to build some kind of message. Another important aspect for me was the format, I started using a DIN A6 sketch book which fitted in my pocket and take everywhere. Since then I have been mainly working with this size of book. This rather small size definitely affects the way I do collage, the way I select the images, and the techniques I use.

This form clearly offers potential that other forms of communication lack

What can collage offer that other forms of communication lack?

EP: For me collage is closer to poetry than to drawing, painting, sculpting or taking pictures. The basic idea is that when doing collage you are saying something new by combining already existing images. Words and images have their intrinsic meanings, but when words or images get together in a white piece of paper these meanings change and acquire a new dimension. In this sense I also see collage very close to play: the combination of images, the game of confronting, making strange, creating contrasts, grouping different scales… is endless, and therefore very playful. I find Collage very gratifying because makes you think a lot, it requires researching, collecting, trying out, surprising oneself…and finally fixing those images to the paper.

Despite its potential in many aspects of his work, it is not something that can be forced or rushed:

EP: Unfortunately, I do not make Collage as often as I would like. Although it can sometimes be a very immediate form, for me collage generally demands a lot of time and a very relaxed environment. At the moment it is an activity reserved for holidays; long days when I can empty my boxes and folders of images on top of the table and start the process.

But in our professional life at the studio, graphic and images collages are often used for conceptualisation or project presentations.

Rory Hamilton is a British designer and teacher, principally in the area of interaction. He has consistently promoted the use collage-type processes in the development and communication of concepts. His development of this form came about through an interesting route:

Rory Hamilton: I originally studied sculpture before getting into design. In the sculpture there are three techniques: modelling (building up a form from a soft material like clay), direct carving (wood, stone.. all about cutting away from a form) and assemblage (building of forms from other objects, girders, bricks, pots and pans, bike saddles). This last form always appealed to me more: it was quick; the materials suggested uses; it was full of metaphor and narrative. So assemblage is to 3d what collage is to 2d. At that time I did loads of collages using 50’s homoerotic photos and tiny drawings blown up on photocopiers, I’d churn out a hundred in a day. The subject matter may have changed slightly (less angst and asses) but the technique remains. It’s always been useful to show an intention in a quick and dirty way.

On his website, Rory encourages the use of “Bad Photoshop.” Is this the same as collage?

RH: Definitely, the “bad” bit of it almost mimics the cuts, tears and juxtapositions of a collage. The intention here is to show what you’re thinking but to imply that it is in progress, can be changed. This is the most important thing; you want people to know that their comments can still help in the development of the idea. If you show super slick “Perfect Photoshop” they might feel less free to criticise, more inhibited because they assume (sometimes wrongly) that what the see is immutable because you seem to have spent so much time on it. Forms of communication such as this offer change, speed, humour, and chance. A way out of the fear a ‘blank page’ staring up at you can bring out.

With this in mind, the collages in this book were created as both response and counterpoint to Jane’s texts in order to help the reader. The playful, haphazard nature of many of the images reflects the way that the pieces are meant to be read, and they way that the images and words are supposed to link. This is further reinforced by the cover image, “Festina Lente,” or ‘make haste slowly;’ Bruce Gernand’s sculpture of the Hare and Tortoise fable. Here Hare, rendered in the slices of a partially resolved digital image, appears to have leapt from the page, or computer screen, to be frozen in a static version of this premature reality. This mirrors the perpetual frustration of the designer in continually having to transform objects from idea and image to reality. In common with many pieces of design work, Hare has apparently launched himself too soon, and as a consequence turns out to be incomplete, half-baked, unable to cope with his surroundings and anxious, perhaps to return to the screen. As an adjunct to this piece, Bruce has created a print that acts as a multi-layered record of its creation. He describes this documentary piece in relation to the Surimono – a Japanese print discipline that incorporates a layering of poetic form; part image, part text, and part paper manipulation. Bruce describes this work as an extension to his sculpture; as a means of jumping from one medium to another, between 2 and 3 dimensions and the perspective that provides on the work. This strikes me as very similar to the techniques used by designers to reflect on their own practice, and with any luck, resolve problems and improve the outcome.

iAdes, Dawn, (1986), Photomontage,Thames and Hudson, London. p.120.

Links:

www.grahamrawle.com

www.mackaoui.com

www.joanbrossa.org

www.chemamadoz.com

www.emilianadesign.com

www.everythingiknow.co.uk