Another review of a bygone fair. Lots of exciting things appearing this year. I will try and add some more photos over time. This is the English version of the piece written in Chinese.

Milan Review 2011

The design world descends on Milan for the annual Fuori Salone.

© Ben Hughes, 2011

In 1961, the inaugural Milan Salone Del Mobile was organised by a committee of local furniture manufacturers in a bid to boost exports as a response to post-war economic stagnation. That initiative proved phenomenally successful. Not only is the fair still going, but as it grew from just 328 exhibitors to over 2,700 today, Northern Italy became the centre for innovative, high quality furniture manufacture. Today, 50 years on, those local manufacturers are joined by competitors from around the world – all conscious that while things are not as bad as post-war Europe, sales and growth have yet to recover their pre-2008 highs and there have since been numerous cutbacks and casualties as a result. To visit the fair, however, is to be protected from these realities to a degree as the mood is always celebratory and the focus on things that are new and exciting.

A visit to the Salone Del Mobile is to be overwhelmed with scale and statistics. How can there be this much furniture in the world? If you spent a modest 5 minutes looking at each stand, and 8 hours a day at the fair, it would take you a month to cover everything. Exposure to this level of content is clearly too much for some. Previous excesses that I have witnessed include a man systematically walking down one aisle after the other of the fair looking at the stands on one side and training a video camera on the other, so that he didn’t miss anything. This year I found a woman waving her video phone around one stand while explaining things to a friend on the other end. Fortunately, you wouldn’t want to spend 5 minutes at most of the stands, and there are vast sections that those interested in contemporary design can ignore completely. For design-watchers outside of the trade, more significant than the success of the Salone is its having spawned the world’s most exciting week-long celebration of product and furniture design – the Fuori Salone. This is a series of over 500 events loosely concentrated around 4 locations in the city. It showcases every aspect of design, from product to textile to lighting to furniture to architecture, and every form of presentation from objects to interaction to performance to installations. Here, there is room for more expression and critique and can be a place of ideas and debate rather than just business.

One of the ingredients that makes Italian design so enjoyable is its ability to provoke. Anyone believing that design can solely address a commercial need should see veteran provocateur Gaetano Pesce’s “L’Italia in Croce” installation. A blood red resin representation of the country, nailed to a crucifix could not be described as a subtle use of metaphor. Its gory and glorious directness is as literal as one could get without actually spelling out this issues it addresses. Fortunately Pesce does this as well in a typed manifesto. Add to this a candle-lit, chapel-like installation with the Italian constitution placed on a lectern and the picture is complete.

In contrast to this provocative and theatrical statement was a retrospective of the man-brand Karim Rashid, also at the Triennale. Some might consider his career a little brief for a major show of this type, but as Karim points out in his opening statement, he is a phenomenally successful designer. Surely he must hold some sort of World Record, with a staggering 3,000 of his products apparently currently in production. Sadly, this success does not always yield engaging results. Indeed the show provides a surprisingly monotonous encounter with the New York based designer’s work. It is hard to imagine how so many bright colours, curves and blobs can add up to such a joyless experience. Impractical, ostentatious and often just plain ugly, it speaks volumes about the perception of volume versus success, and fills one with dread to think that the creator is lauded by many as a maestro of our times. One saving grace of the show is that it highlight’s Rashid’s comparative ability with regard to scale. While a lot of the furniture just seems very unsophisticated in form and finish, much of the product design (watches for Alessi, stationery for 3M), and particularly the packaging design (as with his work with US brand Method) works well. Will Karim have a moment of clarity at his show and decide to stick to the small scale? I imagine he is thinking bigger all the time.

Elsewhere in the Triennale was the second, larger, version of the Yii exhibition which proved so successful last year. This time, along with the Taiwanese designers originally featured are a number of international design stars (Nendo, Konstantin Grcic, Fernando and Humberto Campana) working with the local craftspeople – sculptors, potters, weavers etc. The collection has expanded somewhat and now includes a number of works that take things beyond the traditional materials that it was such a joy to see so expertly worked in the original concept. The maturation of the project will see several pieces go into production in a transition that has been stage managed by Dutch designer and curator, Gijs Bakker. Famous for his role in founding the influential Droog organisation in 1993, Bakker has successfully bought the work to an international stage, but this growth may have been at the expense of the unique and novel aesthetic that was achieved with the initial project. No doubt this is linked to an economic imperative, and it will be interesting to see how this strategy fares.

Bakker’s uncomfortable ideological split from his co-creation, Droog design, in 2009, has left the company in a strange position. In line with their focus on retail, over half of the stand at this year’s show was given over to a shop. The remainder was a set of designs from modular parts that was heralded as a revolution in design, technology and distribution, entitled ‘Design for Download.’ This proposes a networked system of production, customisable by consumers and locally produced through rapid manufacture processes. This oft-visited theme seemed strangely out-of-touch for a company that has been responsible for so many innovative projects in previous years. There have been countless experiments in this area for more than a decade and the furniture proposals did not inspire one with new possibilities. Conversely, their rudimentary construction and familiar palette only seemed to reinforce the limitations of the technology.

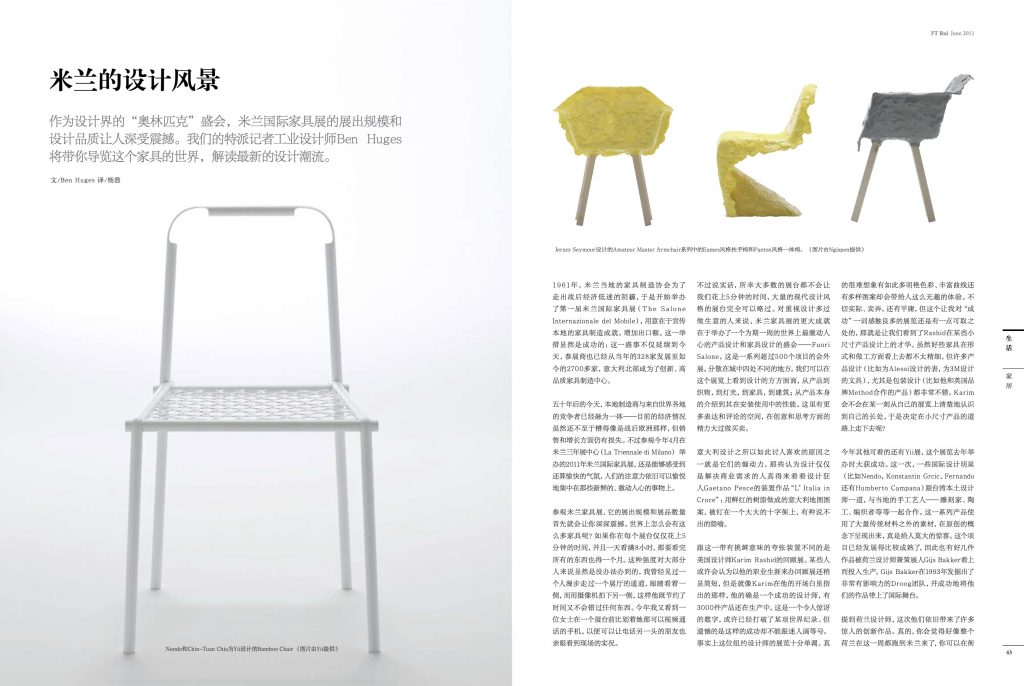

Despite this uncharacteristic blip, there were many instances of fabulously inventive work from Dutch designers at the fair. Indeed, one could be forgiven at times for thinking that the whole nation had decamped to Milan for the week as Dutch could be heard in the streets, restaurants and bars all over the city. In Zona Tortona, Ngispen was drawing big crowds with a mixture of old and new designs from some familiar names. The brand is a contemporary domestic furniture division of Gispen, one of the largest office furniture companies in The Netherlands. Ngispen’s art director, Richard Hutten is the ideal person to lead this brand, having a long association with the new wave of design emerging from the Netherlands since the 1990s. A graduate of the design academy, Eindhoven, Hutten started his studio in 1991. He then came to prominence through work with Droog and subsequently Moooi (Marcel Wanders’ company). He continues to run his own design studio, but in 2009 he had the opportunity to splice his own self-edited Richard Hutten Collection into a new enterprise alongside Ngispen. The mutual benefits of this arrangement is evident in that Hutten’s network has allowed him to call on the talents of James Irvine, Dick van Hoff, Jurgen Bey to create work for the new collection. These are augmented with the reissue of older pieces from the likes of Gerrit Rietveld and company founder WH Gispen.

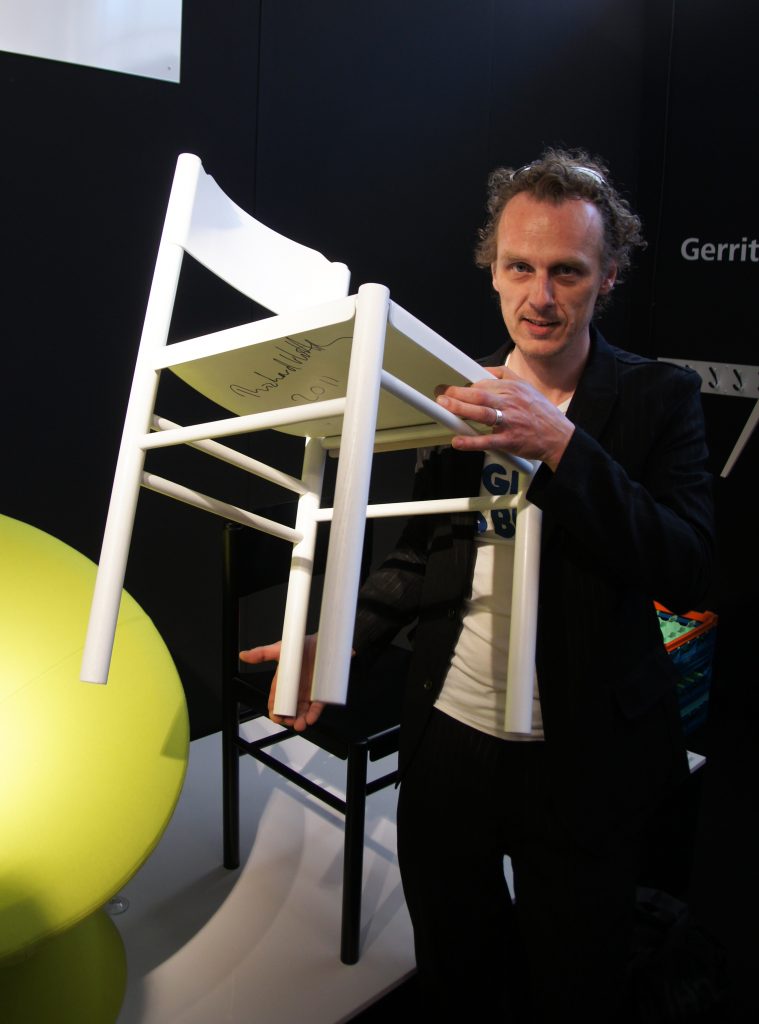

This year’s collection includes one of Hutten’s own creations, a chair he designed for the Zuiderzee museum. It is a reinterpretation of a turned wooden chair, with the added innovation of a tightly radiused plywood panel in place of an upholstered seat. Also on own show, in response to the loose title “Playing with Tradition” are works by several well-known figures including Jerzy Seymour and Maarten Baas. The latter is the first ‘mass-produced’ chair by the Dutch designer, famous for his work with challenging and highly labour-intensive production techniques (burning and sculpting, amongst others). In order to accommodate the designer’s commitment to hand-made, individually distinct pieces, this chair “More or Less” bears his signature in the sketched outline of the seat and back, giving the impression of a completely unique piece. The chair itself is a relatively familiar plywood form sitting on a tubular steel base, but the effect of seeing two or three together is clearly reminiscent of Baas’s more intricate studio pieces.

Jerzy Seymour’s work, entitled “Amateur Masters,” represents an exploration of familiar chair typologies through novel materials and rudimentary manufacture processes. Seymour tells me that he saw no problem with the furniture forms that the Modern Movement had given us, but that the system of manufacture needed to be challenged. This collection, a reworking of an Eames-style armchair and a Panton-style one-piece chair (soon to be joined by an interpretation of Jasper Morrison’s Air Chair), is made on a basic mould using a biodegradable polymer made from 60% wax, 20% talcum powder and 20% tapioca starch. This dubious sounding recipe results in a form that either looks half-finished, or half-melted but is surprisingly fully functional. The Berlin-based designer is confident of its performance: “We stuck it outside for a hot Italian summer and it didn’t melt or degrade, and the armchair has actually been subject to the same stress-testing as an equivalent Eames chair.”

Novel production methods such as this are an obsession with contemporary designers looking for alternatives to mass production in order to see their creations realised. The traditional road to success of developing a working relationship with a major manufacturer is so congested that many young designers spend time coming up with ways of circumnavigating it entirely. One such project was presented this year as part of the Eindhoven Academy show. Stuck out in a location devoid of passers-by, this quickly established itself as one of the Fair’s must-see events, sticking out as it so often does from the majority of school shows for its consistent professionalism and spirit of inventiveness. Dirk Vander Kooij’s “Endless Chair” project uses a decommissioned industrial robot to ‘print’ chairs at a rate of one every 3 hours. He explained that his (Chinese) robot, nicknamed “Herman,” was purchased from an importer after borrowing one to test the concept for his degree project. The innovation lies not just in the design of the chairs, but also in the print-head extruder which Vander Kooij had to design and build himself. The plastic, which turns out to be derived from recycled fridge linings, is squeezed out of the extruder like toothpaste to build up the chairs’ shape, giving them their distinctive look. The versatility of such a production method means that Vander Kooij can vary the colours, size and even shape of each chair simply by altering the plastic mix or software controlling the robot. In redesigning the production method, the designer successfully highlights the problems with existing strategies (such as Droog) which are working with smaller scale (albeit more precise) technologies, as well as the potential for repurposing sophisticated technologies such as Herman after retirement from their original use.

The chance to see the ideas and experiments of these emerging design talents is the main draw of the fair for the majority of visitors, but it is also a chance to revisit the work of their predecessors, either in the showrooms of Brera, the stands of the Salone, or the excellent, recently remodelled Design Museum in the Triennale. But the greatest treat for any fan of design has to be a visit to what might be considered the fountainhead of all that is fun, irreverent, experimental and exciting about contemporary design, and Italian design in particular – The Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni. Since his death in 2002 and subsequent opening to the public in 2006, Achille Castiglioni’s studio has become a place of pilgrimage for fans of design from the world over. I have been lucky enough to visit on several occasions, and each time discover new and unexpected things.

This is not a museum of any kind you have visited before. You might be greeted at the door by Castiglioni’s wife Irma, his daughter Giovanna or his long time design associates, Antonella or Dianella. Each has a unique insight into the work of the designer and the collection of the museum, and each possesses an enthusiasm and jollity that keeps the spirit of the famously playful designer very much alive.

In some ways it is still a working studio – when not open to the public the staff are hard at work cataloguing and archiving the vast collection of project work, prototypes and “anonymous objects;” those gadgets and novelties which the designer delighted in demonstrating to friends, clients and students. Each one of this collection of found or donated things demonstrates an inventiveness, novel observation, or twist that echo the work of the designer. They encourage an unconventional view of the world which seems to be a starting point for much of Castiglioni’s own design work. This incorporates everything from architecture to cutlery, but the Castiglioni name is most associated with furniture and lighting design – created over a period of 40 years, much of it through long associations with companies emerging during the same period, particularly Zanotta and Flos (for whom he created such iconic pieces as the Mezzadro chair and Tioi Lamp). His daughter, Giovanna explains the importance of her father’s relationship with industry: “In those days it was really nice because the companies and designers grew up together. Milan was a little city, so everyone knew everyone else – there were few architects. There was not so much competition as today.” But this did not mean that projects were any easier than they are today. If anything, they took much longer because of the research involved: “I think Achille started every project from the beginning and made first a big research about other objects around because it was really important to learn from this – he loved so much to be careful with every detail and studied people most of all. He was so curious. He just kept his eyes open. If you imagine if you have to design an ashtray – he was a heavy smoker in this case so he understood that an ashtray needs to hold a cigarette horizontally, so he studied how to achieve this in a way that is also easy to clean.” This is in reference to the Spirale ashtray. “ … but also he had a wonderful relationship with workers and engineers. For him they were so important and he would study with them the processes of manufacture. He was really humble and really open and didn’t just send his sketches to the workers and say ok – now you can make it by yourself – No it was every time as a team”

To visit the museum is to get a chance to really appreciate this process, but it is not uncommon to have a strong emotional response, too. A friend remarked to me that during his visit, he had to suppress a compulsion to pick up a pencil and start sketching. This reaction is familiar to Giovanna: “I think that the atmosphere here is quite special. Because you can see where Achille worked for many years, but at the same time you can see and try everything. So it is a good opportunity for everyone to touch the lamps, anonymous objects, the things that he collected during his life and try the chairs. So everybody can absorb something different… In the five years since we opened I can tell you that everybody has a feeling from this studio. Some people are very very sad. I don’t know why. Some people cry. More people are happy – a big percentage are happy!” This ability to impart her father’s philosophy is clearly a great source of pride, and is a way of continuing his teaching: Giovanna cites Konstantin Grcic and Giulio Iacchetti as contemporary designers who share something of her father’s approach, “… but I prefer to say that there is a little Achille in everyone who visits this studio.”

Achille Castiglioni is one of a very small number of designers whose involvement and influence can be felt through every Salone Del Mobile from that first one in 1961 right up to the present day. It turns out that there are ‘about 100’ Castiglioni products still in production, with revivals and reissues appearing every year. Last year saw Tachini reissue the San Carlo armchair, originally produced by Driade, and there are set to be more in the future. This will provide much needed income to enable the newly created Achille Castiglioni Foundation to continue its work, and ensure his collection and ideas are kept alive for the next 50 years and beyond.

Links:

http://www.gaetanopesce.com/

http://www.karimrashid.com

http://www.gispen.com

http://www.zuiderzeemuseum.nl

http://www.ngispen.nl/

http://www.jerszyseymour.com/

http://www.maartenbaas.com/

http://www.richardhutten.com/

http://www.dirkvanderkooij.nl/

http://www.triennale.org/

http://www.achillecastiglioni.it/en/studio.html

Images and captions:

(photos by Ben Hughes unless otherwise credited)

2011_Milan_13_Wednesday_Richard_Hutten.JPG

Richard Hutten with his Zuiderzee Chair for Ngispen

2011_Milan_13_Wednesday_Jerzy_Seymour.JPG

Jerzy Seymour at Ngispen stand with his Amateur Masters Chairs

2011_Milan_13_Wednesday_Tortona186.JPG

Festival atmosphere on Zona Tortona Bridge

Yii54_Bubble Sofa 2.jpg

Bubble Sofa by Yu-Jui (Kevin) Chou with Su-jen Su

Photo: Yii

Amateur Master Arm_3.JPG

Amateur Masters Armchair by Jerzy Seymour

Photo: Ngispen

Amateur Master Arm_2.JPG

Amateur Masters Armchair by Jerzy Seymour

Photo: Ngispen

Amateur Master S_3.JPG

Amateur Masters Armchair by Jerzy Seymour

Photo: Ngispen

More or Less chair_2.JPG

More or Less Chair by Maarten Baas

Photo: Ngispen

Zuiderzee Chair_3.JPG

Chair for Zuiderzee Museum by Richard Hutten

Photo: Ngispen

Dirk Vander Kooij with his robot “Herman” and furniture from his project “Endless”

Photo: Dirk Vander Kooij

2011_Milan_15_Dirk_Vander_Kooij.JPG

Dirk Vander Kooij with his robot “Herman” printing a chair.

2011_Milan_15_Friday_Dirk_Vander_Kooij2.JPG

Dirk Vander Kooij with his robot “Herman” and furniture from his project “Endless”

egon_vander_linden_6.jpg

Low Chair by Dirk Vander Kooij, produced by “Herman” the robot

Photo: Dirk Vander Kooij

Vivid_Rotterdam_2.jpg

Rocker by Dirk Vander Kooij, produced by “Herman” the robot

Photo: Dirk Vander Kooij

bamboo-steel_chair01_NENDO.jpg

Bamboo Steel Chair by Nendo and Chin-Tuan Chiu for Yii.

Photo: Yii

bamboo-steel_chair08NENDO.jpg

Bamboo Steel Chair by Nendo and Chin-Tuan Chiu for Yii.

Photo: Yii

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_04_Giovanna.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni, with his daughter, Giovanna

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_35.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: prototypes and experiments

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_67.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: studio with prototypes and chair collection2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: studio with prototypes and chair collection2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_35.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: prototypes and experiments

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_67.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: studio with prototypes and chair collection2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: studio with prototypes and chair collection2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_69.JPGStudio Museum Achille Castiglioni: “Mezzadro” and “Sella” stools

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_59.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: desk

2011_CastiglioniMuseum_50_anonymous_objects.JPG

Studio Museum Achille Castiglioni: part of the collection of “Anonymous Objects”