An interview and review of the Rams’ retrospective at the Design Museum in 2010. Published in Blueprint March 2010. The article is formatted as a review which is a shame as I would have like to have included more of the interview.

photo Luke Hayes

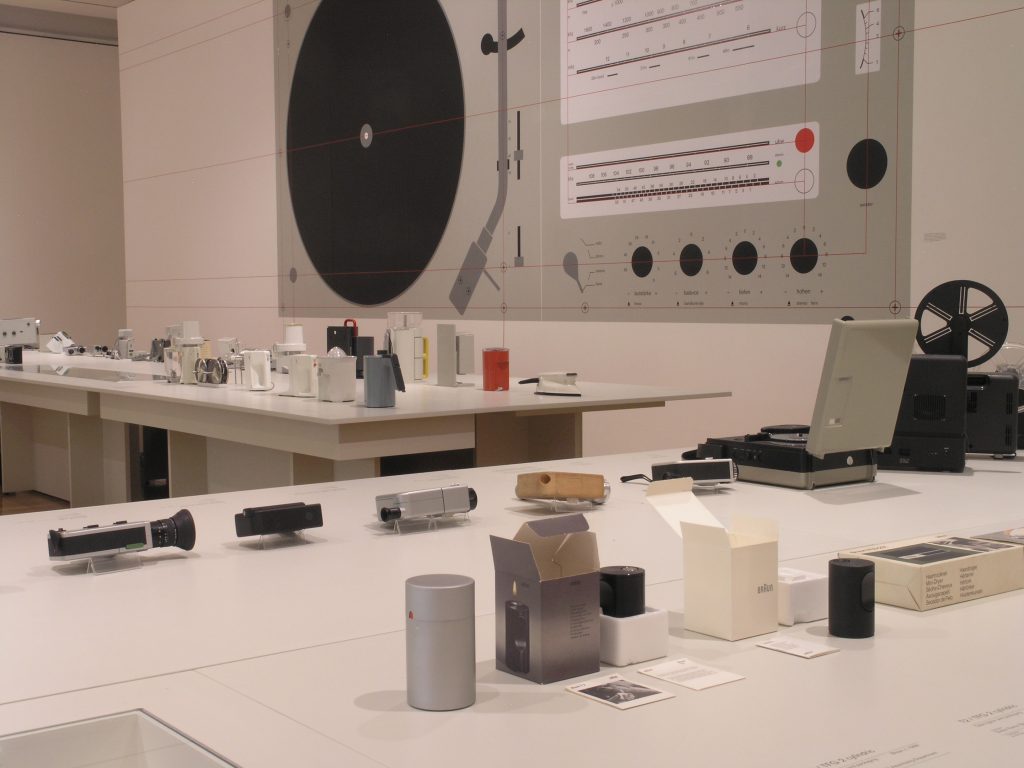

This retrospective of Dieter Rams’ work is a must-see for anyone interested in how the product language of the moment came into being. Twenty years ago, these greys and graphics and grids and grilles were regarded as too formal and too prescriptive next to the playful shapes and colours sanctioned through more expressive mainstream design. Nowadays, designers are falling over themselves to pay homage to the vision, and this exhibition is the fullest articulation of it as you are likely to see.

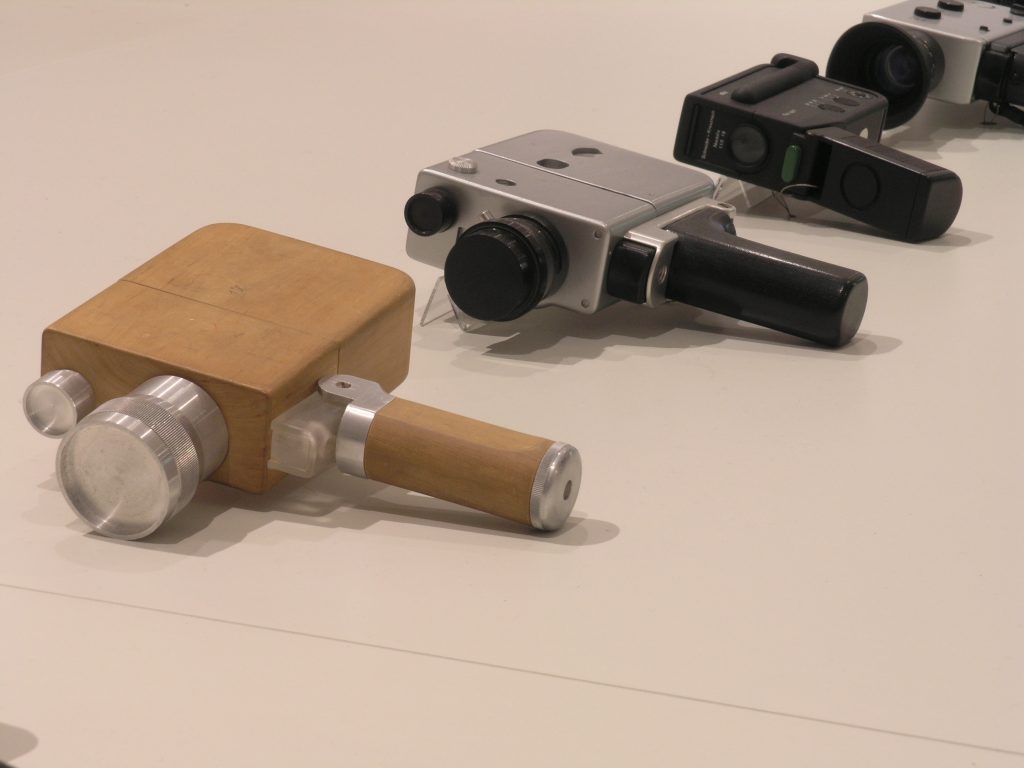

Many of these products were so common that they are instantly recognisable to anyone brought up in the 60’s, 70’s or 80’s. But the exhibition is more than just the greatest-hits. One of the joys is seeing the also-rans in the form of proposals and prototypes that never quite made it. And the also-Rams in the form of the furniture designed for Vitsoe and Zapf from 1957 onwards.

One assumes that this stuff could all just be pulled out of a vault at Braun HQ, or pulled off the shelves in Prof. Rams’ no doubt immaculate garage, but it turns out it took curator Klaus Kemp four years to put the collection together. This was initially for an exhibition in the Suntory Museum, Osaka in 2008, but here presented in a new setting with graphics and layout designed by confessed Rams groupies Bibliothèque.

Out of the 514 pieces that Rams was involved with during his 40 year career at Braun, the one I was most excited about seeing was the TP1. This remains one of the designer’s favourite despite recently celebrating its 50th birthday. Rams’ affection seems to derive from the fact that it was somehow a forerunner of today’s personal stereos, maintaining that “at that time this was the first Walkman.” And that its relative scarcity is down to the fact that the 7” (17cm if you go by the Braun account) records it played were a short-lived medium. I’m not so sure. For one thing, the Walkman was about being on the move, not just portability. Can you really imagine going about your business with a record spinning round dangling from your neck? Also, the 7” single that Rams refers to as the ‘software’ cannot really be deemed a defunct format. I was buying them right through the 1980s and when I last looked you can still get them in HMV. While it may well have been one of the first portable record players, I believe this piece is significant for other reasons. Firstly there is the look of the thing. This was designed at a period when the design team had not fully broken away from the influence of the Ulm school’s stifling methodology, but when the Braun products were developing a coherent language of their own. Many of the formal elements that would be used on later projects are certainly here, but what is most striking is the material. There are components made of aluminium, steel, plastics, rubber, leather. And they all seem to fit together perfectly, in what the exhibition catalogue describes as “A precise collage of materials.” Not only that, but it has a modular construction whereby the radio, amplifier and turntable parts all slot into an aluminium channel. These are then connected with a cable that not only carries the electric signal, but also locks each part in place. It was to be much later when the influence of Japan on Rams’ work would be discussed, but surely here he had created a technological bento box that was pleasing to the senses in several ways. Despite all this, it was never a great success. Rams is not sure how many were made, but it didn’t spend long on the market. Certainly I have had “Braun TP1” as a favourite search on Ebay for over 4 years and not a single alert.

This modularity turns out to be a theme running through the exhibition. Not just in the appliances, but in the furniture too. The 620 Furniture Programme features separate parts that can switch from an armchair to a multi-seat sofa with a low or high back and a base that can accommodate a swivel, castors or feet. This was deemed to be so revolutionary that in 1973 it was granted an “artistic copyright” suggesting that it is an entirely new archetype in furniture design.

Modular construction is something that designers naturally gravitate towards in its clear ability to achieve more with less. More functionality and compatibility with less tooling and wasteful repetition. What the exhibition seems to demonstrate, though, is how poorly this translates in the market. It works well for the Vitsoe 606 shelving system, but apparently not for the TP1, or its proposed siblings, originally intended to include clock and loudspeaker elements amongst others. Even though Braun achieved some modularity in its later audio products, it seems clear from the prototypes and proposals that Rams vision for interchangeable parts went further than this: “I never try to make just one piece, but one that is part of a system where you can add something later on. The first hi-fi equipment or components were not cheap, they were very expensive. So you must find a way that people are able to buy only one piece to start and then to add other ones later. That makes sense for other products, to make a system of products.”

This approach made it to his famous ten principles of design in the form: “A system is better than single element,” but it is implicit in many of the others. Perhaps the most fundamental example of this approach is the Lectron 1102 kit, designed in 1967. This turned the electrical components themselves into modular parts to be assembled on a magnetic surface in order to make different circuits. Rams still feels that this approach is under used. “Today more things could be modular. They are more acceptable in the environments where we live. But it is much more difficult. You have to think about how more elements can be added later. You need an engineering instinct for this.” The exhibition highlights the enduring appeal of this approach, but also its problematic acceptance in practice. With the popularity of this important designer at an all time high, though, maybe we will see more people experimenting with his ideas as well as his aesthetic.

“Less and More. The Design Ethos of Dieter Rams” is at the Design Museum until 7th March 2010

Images (credit: Ben Hughes except where stated):

BraunRams00.JPG Braun TP1 Portable Record Player and Radio, 1959, Dieter Rams

BraunRams01.JPG Braun T 41 Pocket Radio, 1959 Dieter Rams

BraunRams07.JPG Exhibition View

BraunRams09.JPG Exhibition View

BraunRams12.JPG Exhibition View

BraunRams13.JPG Prototype Alarm Clock 1982

BraunRams14.JPG Braun TP1 Portable Record Player and Radio, 1959, Dieter Rams

BraunRams18.JPG Lectron educational toy, 1967, Dieter Rams and Jürgen Greubel

BraunRams19.JPG Lectron educational toy, 1967, Dieter Rams and Jürgen Greubel

BraunRams20.JPG Vitsoe Furniture collection including Chair Program 601/602, 1960, Stacking Units 740, 1974 and Shelving System 606, 1960.

BraunRams23.JPG Dieter Rams

BraunRams24.JPG Dieter Rams

BraunRams25.JPG Design Museum room setting

BraunRams26.JPG Wall-mounted system Audio 1, 1962 onwards, Dieter Rams

BraunRams29.JPG Cine camera prototypes and production models, 1964 onwards.

BraunRams30.JPG Cine camera prototypes and production models, 1964 onwards.

BraunRams34.JPG Works by Sam Hecht, Jonathan Ive, Naoto Fukasawa and Jasper Morrison.

BraunRams36.JPG Audio system 1976–1978 Dieter Rams, Robert Oberheim, Peter Hartwein.

BraunRams49.JPG Exhibition View

BraunRams50.JPG Exhibition View

BraunRams55.jpg Dieter Rams, Photo: Luke Hayes

BraunRams60.JPG Braun TP1 Portable Record Player and Radio, 1959, Dieter Rams

BraunRams62.jpg Braun TP1 Portable Record Player and Radio, 1959, Dieter Rams